The First World War was over by November 1918 and the Special Constables were discharged from the service In March 1919, but were allowed to retain their badge of office.

Special Constabulary badge 1918

(Gloucestershire Police Archives URN 6118)

That same month, Deputy Chief Constable William Harrison gave a detailed account to Standing Joint Committee, of the war work undertaken by the Specials. He first commented that the crime rate in the city was low for the duration of the war then went on to describe the quantity and variety of work taken on by Special Constables in wartime Gloucestershire. Fifty thousand hours, not including court work, were apparently undertaken during this time, most of which was carried out on the beat. Other duties included attendance at public sports events and recruitment gatherings, assisting with the rounding up of military absentees, supervising food queues, guarding entrances to courts and assizes and maintaining a state of readiness in case of air raids. The work of covering Regular police duties was not included in the report in his speech. On 8th April 1919 the following official vote of thanks was sent to each Special Constable: “That the best thanks of the Standing Joint Committee be accorded to the Special Constables of Gloucestershire, for the valuable assistance during the War in undertaking duties of the Regular Police whenever required and thus enabling the policing of the County to be efficiently carried out during the absence, with the Colours, of a large number of Constables”. Shortly afterwards a Specials’ medal was awarded which took the form of a crown with blue and white ribbons and bars according to length of individual service.

The year of 1919 was a year of unrest across Britain, and the second decade came to a close with rioting and strikes that necessitated the re-appointment of a large number of Special Constables to help keep the peace. Race riots were taking place across the country between January and August 1919 and it was feared that they would spread to Gloucestershire. At that time the majority of servicemen had been demobilised and many finding themselves without work accused immigrants of taking their jobs. After eight months the issue was settled, but then The Great Railway strike began on September 26th and lasted for nine days. The Gloucester Echo of the 29th of September reported that eighteen men had been sworn in as Specials in the city of Gloucester, but despite paralysis of the railway, there was a widespread spirit of “carry on” amongst the general population. The following month the Cheltenham Chronicle of the 11th of October reported that a further large number of Specials had been sworn in by the Gloucester police court to assist with unspecified “industrial struggle” and at around the same time, yet more Specials were sworn in at Gloucester Petty Sessions to serve across the county.

The 1920s was a time of strikes and more social unrest, culminating in an all-out General Strike in 1926 and increasing the need to appoint more Special Constables to help keep the peace. The Gloucestershire Echo reported in April 1920 that the Gloucestershire Standing Joint Committee, in anticipation of trouble, approved pay for Special Constables of 10 shillings for 8 hours of duty plus a lodging allowance when away from home. The national coal strike which began in the middle of October, lasted for 17 days and on the 30th October the Cheltenham Chronicle reported that a large number of men had been sworn in as Special Constables in the North Cotswolds, since the strike began. There were fears among the middle classes that the strikes were the work of extremists and Bolshevists who were after a revolution, as had happened in Russia, so in November after the strike was over, the Acting Chief Constable endeavoured to take on more Special Constables as a precautionary measure, in the event of further strikes, but found it difficult to enlist more than just six men at that time.

The year of 1921 began with fears of growing unemployment and the miners came out on strike on 15 April 1921 when the mine owners reduced their wages and increased their hours of work. This became known as Black Friday when the railway and transport unions failed to support them in their action. The Gloucestershire Echo, reporting on a Parish Council meeting that month, commented that extra men were being appointed by the County Council as paid Special Constables to help with the crisis but the individuals selected were already in paid regular employment. As a result, a motion was carried suggesting that the work should be offered preferentially to the unemployed. The year of 1921 had its lighter moments too, with the first local Annual Police Sports day taking place in Cheltenham at the beginning of September and where Special Constable A.F. Franklin won the Special Constables 100 yards dash. At the end of the year unemployment pay was introduced across the country.

During the following four years newspaper stories were dominated by worsening unemployment, which was now costing the country £10 million, troubles in Ireland and three General Elections. With a political swing towards the left there was increased paranoia over Bolshevism and at the beginning of 1924, the ‘Daily Mail’ published a supposed letter from the Russian Communist leader to British communists, urging them to start a revolution. It was a forgery, but it frightened middle-class people, and made them determined to oppose the demands of the workers, thus increasing tensions still further. In February 1924 in Gloucestershire, as elsewhere in the country, there was a railway strike, followed by a dockers strike and a general transport workers strike. The demands were for increased wages and the action created universal disruption until the government patched up a settlement. These strike actions were being taken by working-class people desperately trying to defend their jobs against wage cuts during an economic depression. The incidence of strikes was on the increase which meant a corresponding increase in the need for Special Constables.

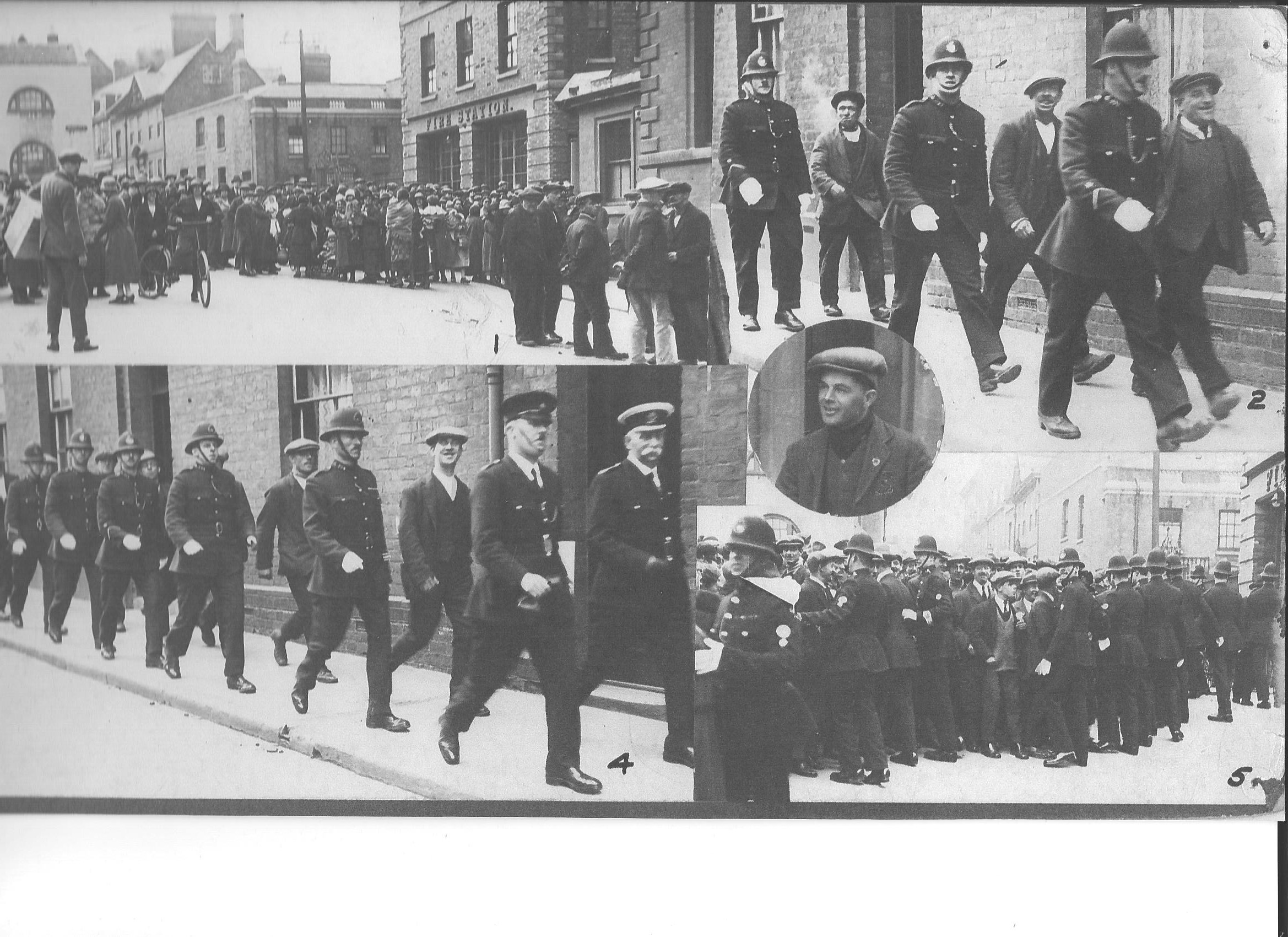

Gloucester canal and bargemen going to prison for various offences – Picketing, Obstructing the Police etc in the General Strike 22 May 1926. Led by Deputy Chief Constable Hopkins, Inspector Williams from the Police Station at Bearlands to Gloucester Prison.

(Gloucestershire Police Archives URN 1874)

At midnight on the 3rd May 1926 the General Strike began. All workers took part in an action that affected the whole country and in Gloucestershire, 152 of the first police reserve and 130 Special Constables were appointed to help keep the peace. After nine days, all the strikers except for the miners went back to work. The miners continued to stay out and police including Special Constables were required to supervise the Forest of Dean miners, although there was very little trouble and the strike action eventually folded. Following on from the General Strike, Chief Constable and the Chairman of the Standing Joint Committee for Gloucestershire gave an official vote of thanks to the Special Constables thanking “all those who came forward to help the police during the national emergency”. In addition, the Specials received a letter from the Prime Minister (Stanley Baldwin) and the Home Secretary for having given their services during the “recent crisis”. However, twelve months later, the town council and the Standing Joint Committee were still in dispute as to who should bear the £5,949 worth of costs incurred as a result of the strike. 1926 represented a unique moment in history, as in 1927 the Trades Disputes Act was passed, which made general strikes illegal.

In 1930, local newspapers reported on the issuing of 63 long service medals to Special Constables with over ten years of service, some of it during wartime. The constables were from Upton-on-Severn, Tewkesbury and the surrounding villages. At the beginning of 1931 an estimated £179,855 was approved by the Standing Joint Committee for expenditure on the Police Service, with £3,070 earmarked for the Constabulary Reserve and just £20 for the Special Constables, who were unpaid, apart from occasional out of pocket expenses, and were also largely untrained. In recognition of the contribution that Specials had made to Gloucestershire policing, in July of that year, the Chief Constable Major FL Stanley Clarke presented long service medals on behalf of the Home Office, to a significant number of Special Constables across the county. The conditions under which the medals were granted were that the recipient had to have served in the Special Constabulary reserve for not less than nine years and should have been recommended by the Chief Officer of Police as willing and competent to discharge the duties of a Special Constable, without pay, during that period.

In 1932, the country was in deep depression and unemployment was at its highest. The Regular Police received two pay cuts and were reportedly resentful that they would have to teach Special Constables to undertake some of their work for no pay. In response it was affirmed that the training of Special Constables was limited to their role in emergencies and Specials were not intended to replace Regulars. However, the country’s financial situation failed to improve over the next few years and in 1935 it was reported that Gloucestershire Police were unable to increase the size of the Regular Force to the required number to cope with the increased demands resulting from extra traffic duties. Traffic duty was considered unsuitable for untrained Specials and at the same time, the Constabulary could not afford to make use of its paid reserve. On a sunnier note, that same year, Head Special Constable Captain GB Limbrick from Stroud was one of 30 members of the Gloucestershire Police Force, to receive The King’s Jubilee Medal.

By 1936 with the threat of war moving ever closer the shape of the Special Constabulary began to change. With the weeding out of less committed individuals and the provision of more training there was a general rise in standards and Specials began to take on traffic and other duties. To join the Special Constabulary in Gloucestershire men had to be British subjects aged between 20 (later increased to 30) and 65, physically fit and with good eyesight. In their first year, Special Constables were expected to undertake a minimum of ten duties per year and in subsequent years, a minimum of five. The Government Anti-Gas School was set up in 1936 for educating both civil and police instructors on what to do in the event of a gas attack. It was located at Eastwood Park in Falfield.

In 1938 a major initiative was proposed by Chief Constable WF Henn to reorganise the Special Constabulary, which up to that point had existed as an out of date list of 1,700 individuals. The aim was to recruit sufficient men to serve as Specials within a separate Constabulary parallel to the Regular Constabulary and numbering 3,000 in strength. Special Constables were to receive training specific to their war work as well as training in general police work in order that they could cover for members of the Regular Police Force who were called up to the Armed Services. Initially it was proposed that the Special Constabulary remain mostly non-uniform except in the cities of Cheltenham and Gloucester and that they would continue as an unpaid service.

The first of many localised gatherings of the Special Constables Association in Gloucestershire was set up in Moreton-In-Marsh in October 1938 with a remit to promote education, training and good fellowship through leisure pursuits. In January 1939 Colonel JL Sleeman was appointed Chief Special Constable to begin the reorganisation of the Special Constabulary and supervise recruitment and training, but by the end of July the number of Specials in Gloucestershire still fell short of the target. The comprehensive training that the Special Constables received had to be undertaken during their spare time and it continued throughout the war. All Specials were part-time and undertook twelve hours of mandatory peacetime training per year. During the first few months of 1939, before the outbreak of war, mimic air raids in which Specials played their part, took place at different locations within the county. When war was finally declared on the 3rd September, there was a surge of volunteers who wished to enlist as Special Constables, finally bringing the required number up to full strength.

In 1939 the men were starting to be trained for their war duties.

This photo shows the men of the Hopewell Street Section, they were trained by Police Sgt 180 Walter Ryland (back row in uniform), the men had no uniform issued until about 1941.

Sat front centre is Special Supt John Newth, and on his right is Special Sgt Hobbs.

(Gloucestershire Police Archives URN 6932)

References

- Information taken from various newspaper articles accessed on https://www.findmypast.co.uk/

- Thomas Harry. The History of the Gloucestershire Constabulary 1839 -1985. Published by Gloucestershire Constabulary 1987

- The General Strike 1926 https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zsxyhv4/revision/2

- Gloucester Archives D37 Correspondence of Maynard W Colchester – Wemyss 1903-1925 to the King of Siam Rama VI. Item D37/1/342

- Gloucester Archives Item D10423/Box 28/110 Printed pro forma letter to F P Hart from the Prime Minister

No Comments

Add a comment about this page